C H A P T E R

N ° 41

Submarines (Part 2)

Submarines are primarily recognized as military vessels, yet their role has evolved significantly in modern society. They now, additionally, function as crucial analogue environments for space missions, facilitating the testing of human endurance, isolation, and life support systems—such as CO2 scrubbers—in extreme underwater conditions. This research is instrumental in shaping future explorations of the Moon, Mars, and beyond. Moreover, submarines serve to assess autonomous navigation and remote sensing technologies. To support this research, they depend heavily on services like the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), including the Global Positioning System (GPS), as well as satellite communication services. In summary, while certain submarines continue to serve military purposes, others operate as advanced laboratories, leveraging space-derived technology and addressing the human and technological challenges inherent in, for example, space exploration and rural places on Earth.

“ An analogue environment is a real place on Earth with conditions (geological, environmental, or biological) similar to a target destination, like Mars or the Moon, used for studying planetary processes, testing space technology and protocols, and training astronauts for space exploration. “

In Hoplon’s previous article on the relation between space weather and submarines; C H A P T E R N ° 40 Submarines (Part 1), we looked closer at the relation between space weather, critical space infrastructure, and submarines. Today’s article will be the second part, and thus the last, of two articles focused on the relation between space weather and submarines. Combined the articles explore the impact of space weather on the submarines, looking closer at the interdependencies between critical infrastructure and the risks and vulnerabilities they pose to submarines.

In this article; C H A P T E R N ° 41 Submarines (Part 2), we will look closer at the relation between space weather, the energy sector, and submarines.

Submarines and the energy sector

Submarines depend heavily on the energy sector for their power, relying on either nuclear fission (for long-range nuclear submarines) or diesel-electric systems (using diesel fuel to charge massive batteries for conventional submarines) to generate electricity for propulsion, life support, and all onboard systems. Ongoing research is, however additionally exploring alternatives like hydrogen fuel cells for greater underwater endurance. Their fundamental need for consistent power sources, whether nuclear fuel or diesel, connects them directly to these energy technologies, impacting range, stealth, and operational capability.

“ Nuclear fission is a process where the nucleus of a heavy atom (typically Uranium-235 or Plutonium-239) splits into smaller nuclei, releasing immense heat, radiation, and additional neutrons. “

Nuclear-Powered Submarines (SSNs/SSBNs) utilize nuclear reactors (fission) which provide immense heat, creating steam to turn turbines for propulsion and generate electricity. This offers virtually unlimited range and speed without refueling for decades. They rely on the nuclear fuel cycle, a specialized part of the energy sector, for their core power, as the submarines need secure, high-grade nuclear fuel.

Diesel-Electric Submarines (SSKs) run on diesel fuel from the oil sector to generate electricity, charging large battery banks, which then power the submarine underwater. They need frequent access to fuel, often needing to snorkel or surface, and are limited by battery life, tying the two conventional fuel supply chains and battery technology.

Other advanced and future systems are, for example; ‘Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP) and Batteries’. Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP) is technology enabling non-nuclear submarines to stay submerged for weeks by generating power without atmospheric oxygen, in contrast to diesel-electric submarines that need snorkeling. This technology improves stealth and underwater endurance by allowing them to run on stored energy sources like fuel cells or Stirling engines, using liquid oxygen (LOX) or high-test peroxide, making them virtually silent and harder to detect than nuclear submarines.

“ Fuel cells are electrochemical devices that convert the chemical energy from a fuel (e.g., hydrogen) and an oxidant (e.g., oxygen) directly into electricity, heat, and water. This is without combustion, making it operate like a continuously fueled battery for efficient, clean power generation for e.g., submarines. “

“ Stirling engines are external combustion heat engines that convert heat into mechanical work by cyclically heating and cooling a sealed, permanent gas (e.g., air, helium, hydrogen) in a closed system, causing it to expand and contract, driving pistons. “

“ Liquid oxygen (LOX) is the clear, pale cyan liquid form of oxygen (O2) produced by cooling gaseous oxygen to extremely low temperatures, making it a dense, manageable way to store large amount of oxygen for industrial, medical, and aerospace uses. It is a powerful rocket propellant and breathing supply. However, it significantly accelerates combustion and requires specialized cryogenic handling. “

“ High-test Peroxide (HTP) is a highly concentrated (~85-98%) form of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) used as a powerful oxidizer and propellant, especially in rocketry due to its ability to decompose into hot steam and oxygen, offering advantages over cryogenic fuels due to its storability and non-cryogenic nature. However, it is hazardous and requires careful handling. “

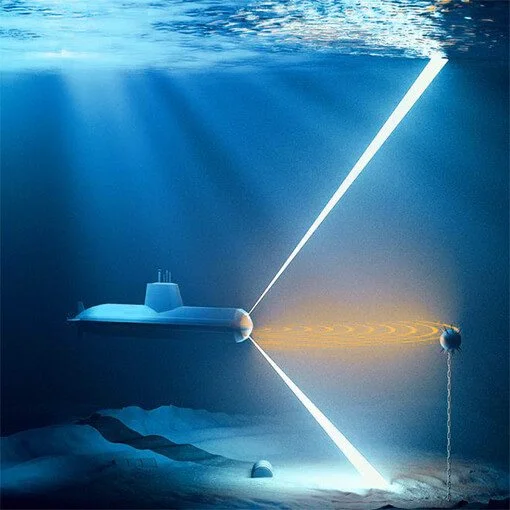

Targeting and obstacle avoidance (Sonar)

To avoid obstacles or for targeting, submarines use passive and active sonar. Passive sonar listens for sounds like engines and propellers from other vessels, crucial for stealth, whereas, active sonar emits pings and listens for echoes to find objects. The latter does, however reveal the submarine’ presence.

The submarine use electricity to power both active and passive sonar. They use electricity to power active sonar to create sound pulses, whereas electricity is used for passive sonar to process the sound signals received by hydrophones. Submarines generate large amounts of electricity from nuclear reactors or diesel engines to run all their systems. This includes sophisticated sonar suites, which are vital for navigation and detection underwater.

In essence, submarines are complex energy consumers, and their design, range, and stealth are dictated by the available energy sources, linking them closely to various facets of the global energy industry, from nuclear fuel to diesel and advanced battery technology.

Space weather and the energy sector

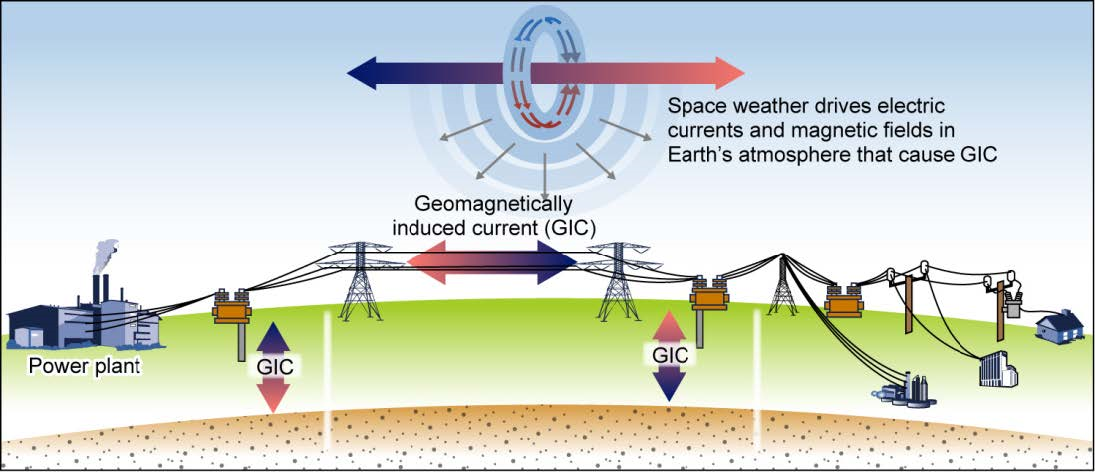

Space weather can severely impact the energy sector by inducing damaging currents, called ‘Geomagnetically Induced Current (GICs)’, in long power lines, causing overheating and destroying transformers, creating grid instability, triggering protective shutdowns. Additionally, space weather can disrupt satellite services crucial for grid management, potentially leading to widespread, long-term blackouts.

Here are three ways that space weather can affect the energy sector:

Power grids: Vulnerable long-distance transmission lines and large transformers are most at risk, with potential for widespread, sustained outages caused by geomagnetic storms.

Pipelines: Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs) can affect pipelines, causing operational issues and corrosion.

Satellite systems: Energetic particles and radio blackouts disrupt capabilities enabled by things such as the Global Positioning System (GPS) and satellite communications, essential for grid monitoring and operations.

The energy sector and submarines

A total shutdown of the energy sector would paralyze conventional diesel-electric submarines by cutting fuel/power. Nuclear submarines relying on onboard reactors would, however, be less affected for propulsion, yet still need shore power for non-propulsion needs in port, which would make them experience logistical chaos for crew, supplies, and command/control, ultimately limiting their long-term operational independence and mission effectiveness due to severe dependency on external support systems.

An immediate power loss on Diesel-Electric Submarines (SSK) would mean no diesel (i.e., fuel) or electricity. This would lead the engines to stop, batteries eventually getting drained, and ultimately – if not acted upon – leading the submarine to lay still/dead in the water, making it vulnerable. Furthermore, a shutdown of shore power also means that batteries cannot be recharged, consequently severely limiting submerged endurance.

The impact on Nuclear Submarines (SSN/SSBN) are slightly different. The propulsion continues short-term, as onboard reactors provide virtually unlimited range and speed at sea, largely independent of the operability of power grids. However, submarines, regardless of operating by nuclear or diesel-electric depends on ports. When Nuclear Submarines are in port, they rely on shore power for non-propulsion needs, such as life support, communications, charging batteries for things like silent operations. A shutdown means these systems fail, consequently limiting time in port. Furthermore, refueling (nuclear), resupplying (food, torpedoes and other parts), and crew support (transport, housing) all depend on the energy sector, making a shutdown of power effect operations. Lastly, global communication networks which are crucial for orders and coordination would collapse without power, isolating the submarines.

The overall effects of a power outage or shutdown of power would cause:

Mission failure: Extended operations become impossible due to the lack of support, even for nuclear vessels.

Strategic disadvantage: Submarines, especially nuclear ones, are power projection tools, making their grounding create strategic gaps.

Vulnerability: According to the U.S. Naval Institute, while at sea, submarines are safe, but returning to a non-functional port or needing resupply would make them extremely vulnerable to disruption or capture.

Space weather awareness

While submarines are less affected by ‘surface’ storms than ships as the deep submersion offers some shielding, space weather poses significant indirect threats via disruption of critical electronic systems (Global Positioning System (GPS), communication satellites, cables) that their assets rely on and other critical infrastructure such as the energy sector.

A loss or disruption to navigation and communication can impact coordination and tracking, and force submarines to rely on internal systems, or be forced to surface for clear signals, making them vulnerable to potential counterparts. Furthermore, their fundamental need for consistent power sources, whether nuclear fuel or diesel, connects them directly to the energy sector, which comes with its own set of risks and vulnerabilities, consequently impacting range, stealth, and operational capability.

Space weather pose risks to data transfer, with the potential of affecting naval operations. Solar activities such as solar flares and Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) can cause severe impact leading to loss of navigation, communication, and surveillance, consequently reducing situational awareness and communication reliability. In addition, the impact of space on the energy sector would lead to cascading effects within the maritime sector, leading to things such as mission failure, strategic disadvantageous and increased safety risks for submarines.

Space weather may not directly affect submarines and their electronic systems. However, the indirect effects caused through a high dependency on other critical infrastructures can have a significant impact. The risks and vulnerabilities associated with space weather impact should, therefore, be acknowledged and demands an awareness level even in subsectors like submarines where direct effects are not as significant.

Source

Commander G. W. Kittredge, U. S. Navy (1954): “The Impact of Nuclear Power on Submarines”. Proceedings, Vol. 80/4/614. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1954/april/impact-nuclear-power-submarines

Grant, Alan (2012): “The effect of space weather on Maritime Aids-To-Navigation Service provision”. Annual of Navigation 19(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/v10367-012-0005-9?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

ESA (2024): “Submarines for space”. Science & Exploration. https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Videos/2024/12/Submarines_for_space

Rajkumar, Hajra; Bruce, T. Tsurutani (2018): ”Chapter 14 – Magnetiospheric ”Killer” Relativistic Electron Dropouts (REDs) and Repopulation: A Cyclical Process”. Extreme Events in Geospace. Elsevier. PP. 373-400. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812700-1.00014-5

James P. McCollough et al. (2022): “Space-to-space very low frequency radio transmission in the magnetosphere using the DSX and Arase satellites”. Earth Planets Space 74. Article No. 64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-022-01605-6

Krausmann, Elisabeth; Andersson, Emmelie; Gibbs, Mark; Murtagh, William (2016): “Space Weather & Critical Infrastructures: Findings and Outlook”. JRC Science for Policy Report. DOI: 10.2788/152877

Baker, D.N; Daly, Eamonn; Daglis, Ioannis; Kappenman, John G; Panasyuk, Makhail (2004): “Effect of Space Weather on Technology Infrastructure”. AGU Vol. 2, Issue 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2003SW000044

J.-C. Matéo-Vélez et al. (2017): “Spacecraft surface charging induced by severe environments at geosynchronous orbit”. Space Weather. Vol. 16, Issue 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/2017SW001689

Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology (n.d.): “Space weather and the Deference sector”. https://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Category/Educational/Pamphlets/Overview%20of%20space%20weather%20and%20potential%20impacts%20and%20mitigation%20for%20Defence.pdf

Australian Naval Institute (2025): “How does submarines navigate?”. https://navalinstitute.com.au/how-do-submarines-navigate/

Fourchard, Gérard (2016): “2- Historical overview of submarine communication systems”. ScienceDirect. Under Fiber communication Systems (second edition). Pp. 21-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804269-4.00002-7

Qu, Zihan et al. (2024): “A review on electromagnetic, acoustic, and new emerging technologies for submarine communication”. IEEE, Volume 12. Pp. 12110-12125. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3353623

Buitendijk, Mariska (2024): “Submarine power plants: potential of new configurations”. SWZ|Maritime. https://swzmaritime.nl/news/2024/08/01/submarine-power-plants-potential-of-new-configurations/

Allied Market Research (n.d.): “Submarine batteries – the powerhouse beneath waves”. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/resource-center/amr-perspectives/energy-and-power/submarine-batteries-market

Brain, Marshall et al. (n.d.): “How submarines work”. Howstuffworks. https://science.howstuffworks.com/transport/engines-equipment/submarine3.htm#:~:text=Submarines%20also%20have%20batteries%20to,power%20to%20run%20the%20submarine.

Rothmund, Marcel (2014): “Underwater”. MTU-Solutions. https://www.mtu-solutions.com/cn/zh/stories/marine/military-governmental-vessels/underwater.html#:~:text=In%20a%20submarine%20with%20diesel,in%20turn%20drives%20the%20propeller.

Zafar, Sayem et al. (2024): “Integrated hydrogen fuel cell power system as an alternative to diesel-electric power system for conventional submarines”. ScienceDirect. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. Vol. 51, Part D. pp. 1560-1572. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.08.370

European Subsea Cables Association (n.d.): “Submarine power cables”. https://www.escaeu.org/articles/submarine-power-cables/

Boteler H., David et al. (2024): “An examination of geomagnetic induction in submarine cables”. AGU. Space Weather, Vol, 22, Issue 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2023SW003687

Hapgood A., Michael (2020): “Is space weather worse by the sea?”. EOS. https://eos.org/editor-highlights/is-space-weather-worse-by-the-sea

Castellanos C., Jorge et al. (2022): ”Does the internet need sunscreen? No, submarine cables are protected from solar storms.” Google Cloud. https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/infrastructure/are-internet-subsea-cables-susceptible-to-solar-storms

Government of Canada (2025): “Space weather effects on technology”. https://www.spaceweather.gc.ca/tech/index-en.php

Gleeson, Jonathan (2024): “Space weather and the impact on submarine cable systems”. VOCUS. https://www.vocus.com.au/vocus-blog/solar-weather-subsea-cables-impacts