C H A P T E R

N ° 39

The Ocean

The relation between space weather and the ocean is an emerging and important researched area. However, there is nevertheless significant research gaps remaining, making it less understood compared to, for example, atmospheric links.

In today’s article, we will, therefore, look closer at the relation between space weather and the ocean, and potential risks and vulnerabilities. Moreover, we will explore direct and indirect effects, looking at things such as the relation between Earth’s atmosphere and the ocean, and how space weather may influence this relation.

Space weather and the ocean

Space weather is a natural hazard originating from the Sun that has the ability to interact with Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere, significantly impacting ecological and technological systems in space and in air, on land, and at sea on Earth.

This natural hazard can interact with the ocean in two ways; directly and indirectly. Its direct impact is primarily on the Earth’s atmosphere, influencing the ocean-atmosphere interactions leading to impact on ocean currents and weather, whereas indirect effects are focused on technology and technological systems.

During Earth-directed space weather events at certain intensity levels, highly energized and charged particles are travelling from the Sun towards Earth. These particles have the ability to interact with the Earth’s magnetic field, penetrating through it, and interact with the Earth’s atmosphere. Here, they create electric currents that cause an instability leading to disturbances to its usual ecological order, that can then proceed to effect terrestrial technological systems potentially leading to cascading effects within society.

The ocean is an electrical conductor as it contains dissolved salts (ions) which varies with salinity, temperature, and pressure. This makes it a good conductor, unlike pure water. This means, that the ocean's conductivity itself enhances geoelectric fields near coasts. During space weather events, the highly conductive seawater near coasts concentrates geoelectric fields, making critical infrastructure such as coastal power grids more vulnerable than inland ones. In addition to this, strong geomagnetic storms induce currents (Geomagnetically Induced Current (GICs)) in long conductors, including undersea power and communication cables, potentially causing damage or outages.

Directly impacts

Atmospheric and Ocean relation

Space weather primarily impacts Earth’s upper atmosphere. However, these atmospheric changes can influence lower atmospheric dynamics and ocean-driven currents by altering energy inputs, triggering gravity waves, and affecting upper-atmosphere chemistry, which indirectly impacts weather patterns and the large-scale energy exchange between the ocean and atmosphere. While direct, large-scale oceanographic impacts from space weather are less studied, effects from geomagnetic storms can disrupt satellites crucial for ocean monitoring. Furthermore, solar UV changes can warm the stratosphere, potentially altering tropospheric circulation, which drives ocean currents.

The relation between the atmosphere and ocean is very delicate, meaning that a slight change in the atmosphere can have consequences for the ocean. Space weather has a direct influence on the atmosphere, which consequently leads to an indirect influence on the ocean. The influence on the Earth’s upper atmosphere affects atmospheric winds, influencing ocean eddies and larger weather patterns, such as winds driving currents.

Space weather influences the Earth’s systems by ejecting charged particles and radiation towards Earth. This disrupts Earth’s upper atmosphere and ionosphere. When the particles enter the atmosphere, they emit heat, consequently warming up the atmosphere. This can affect circulation and influence polar temperatures and the stratosphere, with potential links to weather/climate patterns. Moreover, strong space weather events can trigger atmospheric waves (e.g., gravity waves) that propagate down, potentially affecting lower atmospheric weather. This can, additionally, initiate convection and alter cloud cover.

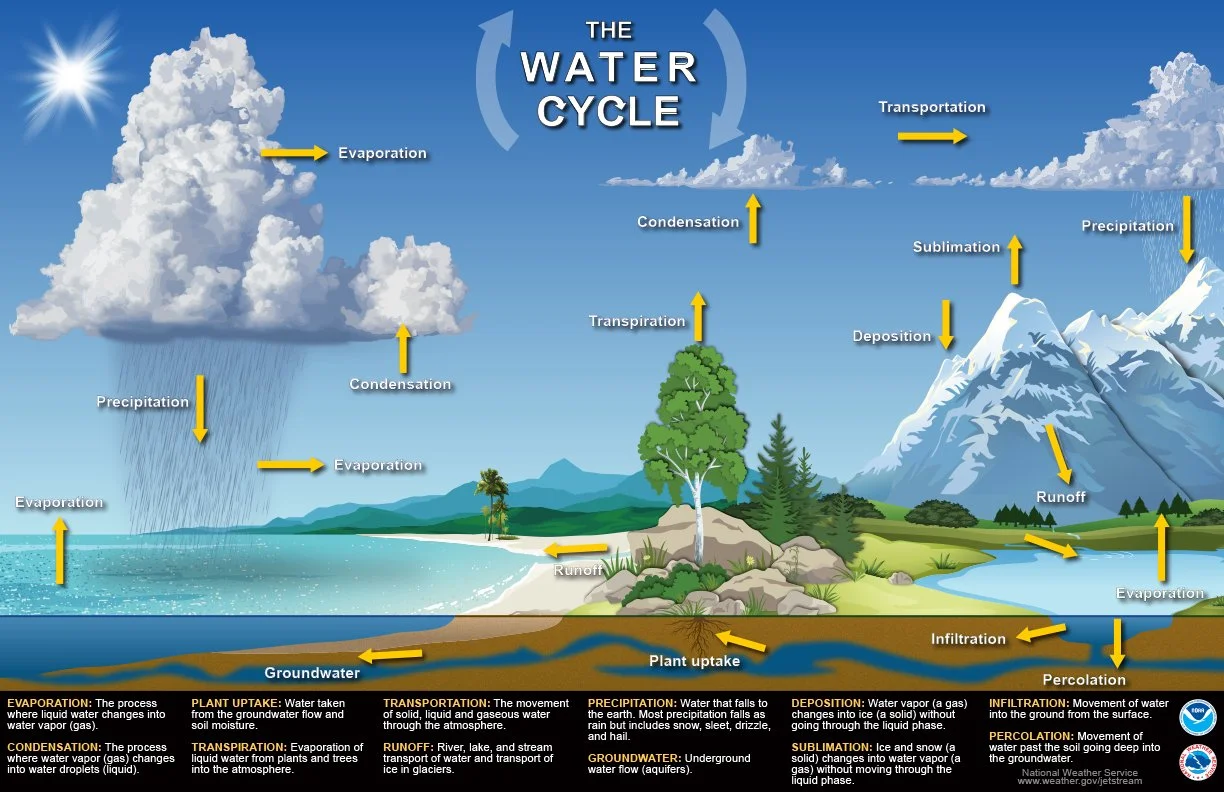

In normal circumstances (i.e., without the presences of a space weather event), the Sun drives the Earth’s water cycle (e.g., evaporation and rain) and ocean currents (e.g., eddies and gyres) through the solar wind, with oceans storing vast amounts of heat. The constant heat and moisture exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere creates a complex feedback loop, enabling the ocean and the atmosphere to influence each other. This relation, for example, decides atmospheric winds and how they push ocean surface waters and create currents, eddies, and waves, with varying strengths influencing ocean dynamics. The solar wind (i.e., solar energy), thus, drives the entire water cycle, starting by its interaction with the atmosphere. This strong relation between the Sun and Earth’s climate may imply, that space weather could subtly alter Earth’s climate and weather systems, though the exact mechanisms are still to be researched.

“ The Solar Wind is a continuous flow of charged particles (plasma (mostly protons and electrons)) streaming out from the Sun’s outer atmosphere (i.e., Corona) at high speeds out into the solar system. “

Hypervelocity impacts

Whilst extremely rare, space weather has the capability to cause hypervelocity impacts by causing satellites to re-enter the Earth. Space weather can increase atmospheric drag on satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) by heating and expanding the Earth’s upper atmosphere (i.e., thermosphere). This increased drag slows down satellites, causing their orbits to decay faster, leading to unexpected and premature re-entries, sometimes disrupting satellite operations and increasing collision risks before planned de-orbiting. Space weather does, thus, not determine the ground impact itself but influences ‘when’ they fall.

The re-entre of a satellite affecting the ocean is, despite being theoretically plausible, said to be extreme unlikely, as most objects burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere. However, the impacts from large space objects like satellites hitting the ocean could include injecting massive amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere, potentially affecting climate, and generating enormous tsunamis.

The re-entrance of satellites into the Earth’s atmosphere can cause water vapor indirectly the following way:

Atmospheric entry: Satellites and rocket parts re-enter Earth's atmosphere, burning up due to friction, creating a trail of vaporized elements like aluminum, silicon, and lithium.

Aerosol formation: These metallic vapors condense into tiny solid particles (i.e., aerosols) in the mesosphere (i.e., upper atmosphere).

Interaction with water: These metal-infused particles provide surfaces for water vapor to freeze onto, affecting ice crystal formation and the size of particles in the stratosphere and mesosphere (i.e., two of Earth’s atmospheric layers).

Cloud effects: This process can influence the water and ice formation in the upper atmosphere, such as the formation and brightness of polar mesospheric clouds (i.e., noctilucent clouds), which are made of ice crystals and are visible in the summer sky. This could potentially alter atmospheric chemistry and cloud cover, especially with the rapid growth of satellite constellations.

“ Noctilucent clouds (NLCs), or "night-shining clouds," are the highest clouds in Earth's atmosphere, forming in the mesosphere (approximately 80 km high) from ice crystals on meteor dust, visible as glowing blue or silver streaks during summer twilight in high latitudes. They appear after sunset when the sun illuminates them from below the horizon, long after the lower atmosphere is dark, and are linked to atmospheric methane and climate change. “

Satellites re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere does, however, have an impact on Earth despite most of them burning up in the atmosphere. While satellites do not ‘add’ water vapor directly, they introduce particles that change how existing water vapor behaves in the upper atmosphere, influencing cloud formation and atmospheric dynamics, that can affect the oceanic dynamics. With tens of thousands of new satellites and other technologies are planned to launch into space, the number of re-entry events is rising significantly. According to researchers in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) – an American authorized peer reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) -, this influx of metallic particles could alter stratospheric chemistry, impacting ozone and cloud properties, potentially leading to affecting Earth’s climate balance. Furthermore, the particles can linger in the atmosphere for decades, increasing upper atmospheric pollution.

Indirectly impacts

Satellites

During space weather events, the Sun releases charged particles and radiation caused by a solar activity occurring on the Sun. Depending on the size of the event, whether the solar activity is fully or slightly Earth-directed, and on the energy level of the particles, more or less particles can penetrate the Earth’s magnetic field. If able to penetrate the magnetic field of Earth, these particles can heat and alter the Ionosphere, Earth’s upper atmosphere, causing density changes and irregularities. Satellites using radio waves to transmit data to receivers on Earth has to travel through this disturbed ionosphere, consequently experiencing errors and delays.

Space weather can, additionally, affect satellites themselves, causing damage and malfunctions within their interior and exterior. This can similarly disrupt communication and navigation systems relied upon by for example the maritime industry.

Navigation:

Geomagnetic storms can increase charged particles in the atmosphere and thereby alter and affect the Earths’ ionosphere. This can distort satellite signals, causing a loss of or inaccurate incoming data. For maritime vessels, this can cause inaccurate or a loss of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and Global Positioning System (GPS) data, making navigation difficult or impossible for vessels at sea.

Radio Communication Interference:

While submarines are generally protected, vigilance is needed as severe space weather events could potentially affect communication. High-Frequency (HF) radio signals, used by marine operators and emergency services for long-range communication, are affected by ionospheric disturbances causing blackouts or degradation, hindering ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship communication. The cutoff of contact isolates vessels, making them more vulnerable to potential threats and disasters.

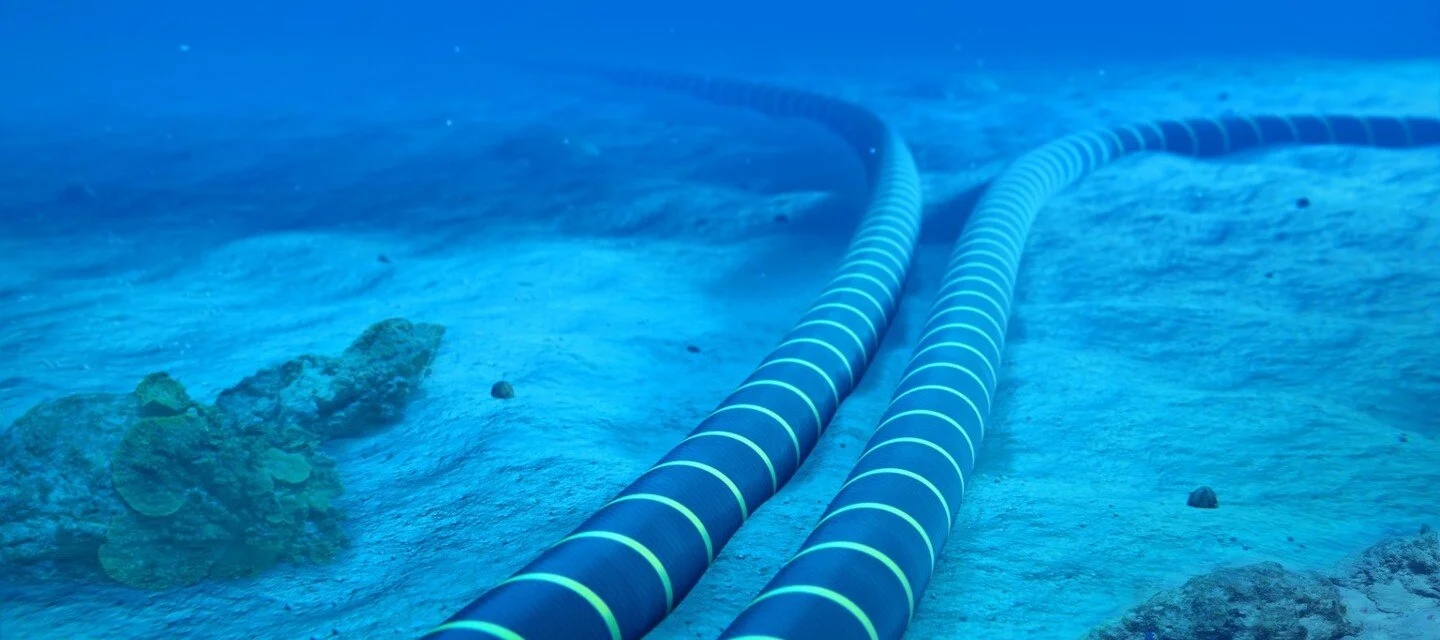

Submarine / Subsea Cables

Space weather, particularly strong geomagnetic storms, generate geoelectric fields that can induce currents (i.e., Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs)) in long metallic conductors, including submarine cables, potentially causing voltage fluctuations affecting internet and communication links. Most systems do, however, have built-in protection.

Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs) in subsea cable copper conductors can disrupt power to optical amplifiers (repeaters). When a solar flare or Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) are strong enough, they can cause rapid changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, including electric currents (i.e., Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs)) in long conductors like submarine cables. The submarine cables use copper to power in-line optical amplifiers (repeaters) that boost signals. However, the Geomagnetically Induced Currents (GICs) caused by space weather can add to or subtract from the existing power feed voltage, potentially leading to overwhelming/causing stress to repeater electronics. The fiber itself is, however, not damaged.

" Power in-line, or powerline, generally means using existing electrical wiring to transmit data or power devices, allowing them to work without separate power cords, like traditional phones getting power from the wall jack or modern devices using powerline adapters for internet over electrical outlets, essentially sending data ‘in line’ with the electricity on the same wires. It can also refer to the literal power cables (lines) that carry electricity, especially high-voltage transmission lines. “

When an optical amplifier gets overwhelmed (i.e., the input power is too high), it experiences ‘gain saturation’, meaning its gain decreases as it cannot amplify further. This leads to distorted, "clipped" signals, increased noise (AESE), potential signal clipping, and instability, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and potentially causing data errors or loss, especially in systems with many channels, making it almost or completely useless.

There is a general agreement between scientists that current submarine cables are fairly resilient to space weather impact with dual power feeds and grounding offering strong protection. An 1859 Carrington-level space weather event is, for example, said to cause a moderate voltage increase (approximately 800 Volts). The impact of applying 800 Volts to submarine cables that are not made for it is, however, quite significant. It could cause serious issues, such as overheating, insulation breakdown, increased resistance, premature failure, or even catastrophic damage (melting/fire), as the increased current could exceed the cable’s thermal limits, leading to rapid degradation and potential short circuit or complete failure. The risk of an event causing such impact is, therefore, evaluated to be a ‘High Impact, Low Frequency (HILF)’ event. Due to this categorization, ongoing assessments/monitoring and mitigation strategies are necessary to be made by cable operators.

Closing remarks

In summary, the most common and significant impact of space weather on the ocean is mainly experienced indirectly through the disruption to technological systems that operates on or above the ocean, rather than direct physical changes to the water itself. However, while space weather does not typically or directly alter ocean currents, it significantly impacts marine technology and safety through things such as communication and navigation interference, and can cause atmospheric changes altering the weather that affects ocean dynamics. Thus, its effects on technology and the Earth’s atmosphere can significantly impact human activities at sea and influences broader Earth systems (e.g., ocean dynamics).

Source

Australian Space Weather Forecasting Centre (n.d.): “Climate Change and Space Weather”. https://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Educational/1/3/3

Murphy, Daniel M. et al. (2023): ”Metals from spacecraft reentry in stratospheric aerosol particles”. PNAS. Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2313374120.

NOAA (2025): “Space Weather”. https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/weather-atmosphere/space-weather.

Met Office (n.d.): ”Space weather impact”. https://weather.metoffice.gov.uk/learn-about/space-weather/impacts.

Kataoka, Ryuho et al. (2022): “Unexpected space weather causing the reentry of 38 Starlink satellites in February 2022”. Journal of Space Weather and Space Climate. Volume 12, id.41. pp. 10. DOI: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/link_gateway/2022JSWSC..12...41K/doi:10.1051/swsc/2022034.

Castellanos, Jorge C. et al. (2022): ”Solar storms and submarine internet cables”. ResearchGate. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.07850.

Boteler, David H. et al. (2024): ”An Examination of Geomagnetic Induction in Submarine Cables”. AGU. Space Weather, Volume 22, Issue 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2023SW003687.

Marshalko, Elena., et al. (2020): “Exploring the influence of lateral conductivity contrasts on the storm time behavior of the ground electric field in the eastern United States”. Space Weather, Volume 18, Issue 3. DOIT: https://doi.org/10.1029/2019SW002216.

Hapgood, Micheal A. (2020): ”Is Space Weather Worse by the Sea?”. Eos. https://eos.org/editor-highlights/is-space-weather-worse-by-the-sea.